I finally saw the olive trees. I had been in Ramallah for over a week, but had been so preoccupied with adjusting to a new environment and finding my way around, I had not even noticed all the twisted trunks and the thin grey-green leaves that filled the city. Until, one day, when I was walking home, an olive fell on my head. At first I reacted with displeasure, as we often do when impersonal forces set out to cause us embarrassment. But when I looked up to find the source of this annoyance, I was suddenly struck with the beauty. Above me was a web of branches and leaves that embodied the life source of this region. And as I began to look around, to look out over the hill upon which Ramallah is set, I realized that the horizon was full of these silent compatriots, whose branches have long been a symbol of peace.

It is well known that olive trees are precious in Palestine. They signify nourishment and wealth, the silkiness of oil, the richness of harvest. Olive trees mature slowly and live for thousands of years. On the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, in the Garden of Gethsemene, there are trees said to have been there when, 2,000 years ago, a man, considered by many to be at least a prophet if not the son of God, prayed that he might be released from his task of dying for the sins of the world. Olive trees have been the quiet witnesses to some of humanity's most beautiful moments and most devastating catastrophes. They are most at home in the sun and soil between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, and number among the inhabitants of this land, which has been loved and contested for as long as history has been written.

In the wonderful documentary film, Budrus, the importance of olive trees to the Palestinian cause and identity becomes palpable. This film has been making its way around the world, and showed last week both in Ramallah and in the Jerusalem Film Festival. I had seen the film in New York at the Tribeca Film Festival, in an audience that included Michael Moore, and it has gained much acclaim, winning awards in San Francisco and Berlin, and receiving special mention in New York, Madrid and Dubai. Budrus tells the story of a village of the same name in the West Bank, which organized and rose up in non-violent opposition when bulldozers began tearing out its olive trees to make way for the Separation Wall. This wall is particularly contentious in that it does not follow the line that is recognized as dividing Israel and the West Bank, but is, instead, built within Palestinian territory, often cutting farmers off from their farmland and olive groves. The film emphasizes the link between olive trees and Palestinian identity when the camera rests on an old woman who says of the trees, “They are like our children!" And as one watches the trees being ripped out of the ground, one is struck with the feeling of having one’s heart torn from one’s chest.

In the village of Budrus, Ayed Morrar helped organize protests against the building of the wall, bringing together a diverse ensemble of stakeholders, including Fatah, Hamas, Israelis and international supporters. His daughter is particularly inspiring as she makes the cause her own and helps organize the participation of the women. The film does an excellent job in showing the hopefulness of this non-violent, popular movement. It also reminds the viewers, however, that the story of Budrus is not unique. Non-violent protest is a marginal, but longtime part of the history of the conflict here. Villages all over, from Bil’in, Jeyyous, Ni’lin, and many more, have become known, at least locally, for their long-term efforts at resistance.

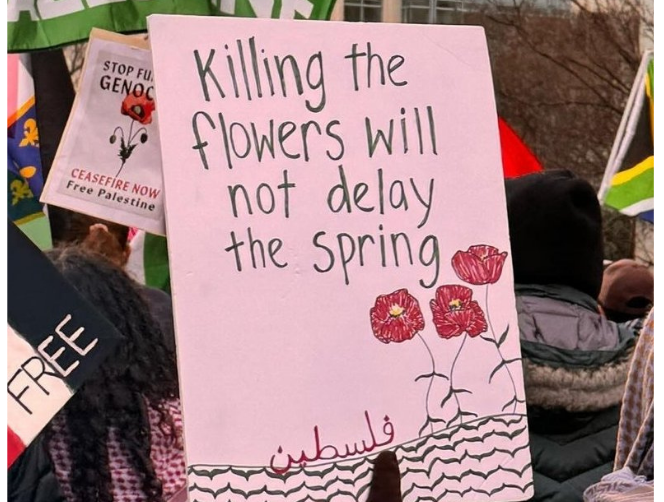

Around the same time I noticed the olive trees, I learned about the concept of "Sumud". In Arabic, this is a word that implies steadfastness. Sumud has been a motto of the Palestinian struggle since 1967. It has represented the quiet willingness to persevere, to not be moved, when all the pressures of the world are trying to force you out of your home and off your land. The concept of Sumud has been interwoven with the symbol of the olive tree, to express the courage to hold one’s ground, and stay strong and rooted. Sumud has also been represented by the image of a peasant mother and child - a mother whose love will not subside, even in the face of hardship and frustration.

Sumud has been a pillar of Palestinian resistance for decades. The first intifada saw many efforts at such non-violent actions, including marches, hunger strikes and civil disobedience. Given this history, it is frustrating when the media characterizes these struggles as nascent and experimental. Nick Kristof’s recent article in the NY Times is particularly disappointing on this point (July 9, 2010). While seemingly supportive of Palestinian grassroots efforts, he reiterates a mischaracterization of the situation by claiming that the root of the failure of these efforts lies on the side of the Palestinians who often begin the stone-throwing, thus compromising their claim to non-violence. Many participants in protests here, however, attest to the fact that tear gas canisters are launched into the crowds of demonstrators without provocation, and the display of force between the Palestinian demonstrators and Israeli soldiers is regularly disproportionate. To chide David for flinging a hopeless stone at Goliath seems to misplace the critique.

Samah Sabawi, on the other hand, writes a beautiful article in the Palestinian Chronicle, where she notes that while people toss around the question of why there is no Palestinian Gandhi, they overlook the extensive tradition of Sumud, non-violence, and the thousands of Palestinian activists and civilians held in Israeli jails and living in refugee camps (http://palestinechronicle.com/view_article_details.php?id=15969). Both individually and collectively, Palestinians have long responded to the occupation through non-violent measures. Protests against the wall, actions against the fences erected between farmers and their land, graffiti, music and marches, have all been among the many attempts to expose and reject the injustices imposed by Israel. Currently, every Friday, Palestinians, Israelis and internationals protest in the east Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah where Palestinian families who have been evicted by Jewish settlers have set up tents in front of their homes, insisting that they will not be moved. The BDS movement, to boycott, divest and sanction Israel, which arose out of Palestinian civil society, is also a crucially important force, which has great potential and deserves international attention.

The most poignant moment in Budrus is when Ayad’s daughter jumps in front of a bulldozer as it is uprooting an olive tree. This incredible act of courage fortunately halts the progress of the bulldozer. But this act reminds us that non-violence requires great risk and unfathomable perseverance. As Sabawi writes, one of the key ingredients for non-violent resistance to work is the attention and support of the international community. Non-violence can only be successful through the external solidarity it garners. In as much as the media feeds on stories and blood and violence, it fails the many who are spending their lives in this steadfast perseverance. Because non-violence rests on the concept of making oneself vulnerable, giving up defenses to expose the violence being threatened by the opposition, it requires the willingness of outside actors to step in and demand accountability from the dominating power. It seems, then, that instead of critiquing the methods of the local organizers or the boys who throw stones, or waiting around for the emergence of a Palestinian Gandhi, the better question may be: What role are you playing in contributing to the peace efforts in this region?

Leah H is a Writer for the Media and Information Department at the Palestinian Initiative for the Promotion of Global Dialogue and Democracy (MIFTAH). She can be contacted at mid@miftah.org.