Israeli occupation authorities adopt several ways of restricting the freedoms and right of movement for Palestinian Jerusalemites. This includes arbitrary arrests and high sentences, in addition to various charges under the pretext of incitement including social media posts. One form of restriction is house arrest, which is especially debilitating for children, who are forced to stay inside their home or a relative’s house, if ordered. Members of the household are then made to sign a pledge to monitor and prevent the child from leaving the house, effectively turning mothers and fathers into prison wardens. The child’s daily activities, meanwhile, are grossly hindered, including basic rights such as going to school or seeking medical treatment, because violating the Israeli court order means being slapped with hefty fines.

There are two types of house arrest: the first obligates the condemned person to remain in his/her house and not leave under any circumstances, for a specific period of time. The second type is that the child/man/woman must abide by a court order stipulating they must remain at a relative’s house, far from their own place of residence. This disperses the family and causes anxiety and tension between the child and the family, leaving them all with social and psychological scars.

Israeli occupation authorities mete out this punitive measure, particularly on Jerusalemite children under 18 and especially those 14 or younger. This is because Israeli law does not allow actual prison sentences for children under 14. Instead, they are placed under house arrest through the duration of the court proceedings, which are often lengthy, until they turn 14 and can be given an actual sentence. The period in which the child is under house arrest is not calculated, even if it is for years or multiple times.

While there have been cases of house arrest since the beginning of 2014, this number began to rise after the wave of protests following the kidnapping of child Mohammed Abu Khdeir in July of 2014. Abu Khdeir was snatched by Israeli settlers, tortured and burned alive, prompting widespread protests, including from other children. The number rose again during the “Jerusalem uprising” in October, 2015 and has continued until this day.

The policy of house arrest has infringed on the personal freedoms of not only children, but all sectors in Jerusalem, including journalist Lama Abu Ghosheh (below, with her daughter Karmel). She spent 10 days in solitary confinement and was released from prison mid-September and put under strict house arrest conditions, which she is still under to this day.

Psychological impact of house arrest:

Professor of sociology, Dr. Bernard Sabella, likened house arrest to the coronavirus pandemic. He said at the beginning of the pandemic, everyone – young and old- were forced to stay at home for at least a month, drastically changing relationship dynamics inside families. Parents assumed their instinctive role as guardians over their children, irrespective of their ages, naturally taking on the role of monitor. “Imagine,” he said, “How they now have to be more than just a guardian. Now they give out orders such as “No going out…no moving around” because they are afraid for their child, afraid they will be taken again, thrown in jail or interrogated.”

Dr. Sabella notes how this situation undermines the relationship between child and parents, especially when the former is deprived of all the activities they are used to, such as spending time with friends and schoolmates or going on trips. This, he maintains, scars the child, who usually becomes much more introverted and sometimes resorts to bad habits such as smoking. The child loses all sense of protection by their own family and is torn from their normal social and psychological environment.

Sabella cites studies that show how institutionalized children or children under house arrest are more likely to commit a felony or resort to violence. He points out that house arrest should be limited to a maximum of two weeks and that the family should be allowed to seek legal, social and psychological counseling if necessary, especially given the long-term effects of this experience.

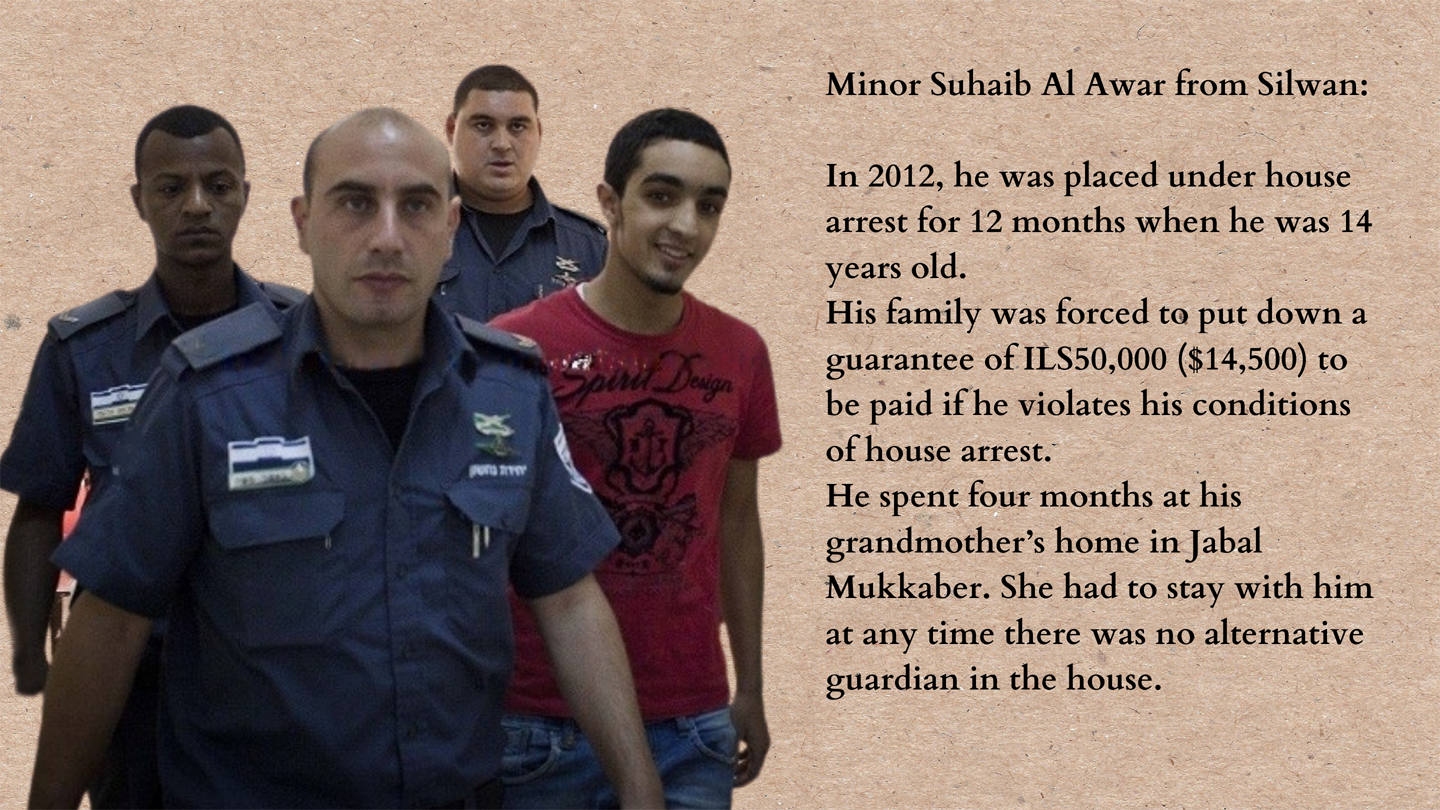

Suhaib Al Awar at his trial

Suhaib Al Awar at his trial

House arrest creates a sense of loss among children of their social security and psychological stability because they are kept in a confined area for days or months without being permitted to leave the house or get fresh air and sunlight. Statistics provided in a MIFTAH factsheet on house arrest indicates that 85% of children in occupied Jerusalem suffered from mental disturbances after being detained or put under house arrest, in addition to suffering physical manifestations such as involuntary bedwetting. According to clinical psychologist, Dr. Murad Amro, some children refuse to go back to school after being under house arrest as a form of rebellion, resulting from their lost sense of security, anxiety and inability to govern their own lives.

Sabella, meanwhile, called for a halt to house arrest for children, pointing out that the policy is in contravention of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Israel signed in 1991. He called for a strong stand and a clear message, saying that any house arrest that continues for over two weeks is in flagrant violation of child rights and in breach of the Convention signed by Israel.

Ali Qneibi, waiting for life to start

Ali Qneibi, 14, sits at a window overlooking the courtyard of his house, which he is not allowed to leave. This is his second house arrest, in March 2022, just five days after his first house arrest order ended.

Israeli occupation authorities imposed conditions on Ali’s second arrest, including an order preventing him from being 30 meters within distance of the Israeli settler who took over a home three meters from the Qneibi family home. This meant that, once he is allowed to leave the house, he will still have to take a much longer road that does not pass in front of the home occupied by the settler.

Ali is always chatting with his friends, who meet to talk with him near this “window to the world”.

This time around, Ali was blindfolded and gagged when he was arrested in the Old City of Jerusalem. He was also badly beaten on the head, neck, belly and face and during interrogation, he was not allowed to eat or drink water. Finally, he was ordered to remain under house arrest for five days.

Ali’s parents

Ali’s father, Rateb Qneibi, who is disabled, said, “Ever since Ali has been under house arrest, he has not been able to participate in any family or social functions, which means someone in the family has to stay with him so he does not violate the order. If he does, his guarantor will be fined ILS60,000 (some $12,000).

His mother, Inas, said, “All of us have become guards and wardens in this prison called home. Ali is the prisoner and we are his prison wardens. Imagine how hard it is to be a prison warden to your own child just because you are forced to carry out the [Israeli] occupation’s orders?”

She continued, “Ali has every right to live a normal life. He has a right to go to school, to play with his friends and to come with us to family functions. The [Israeli] occupation has deprived our son of all these things. He is still under house arrest…but before this, every time something happens in the neighborhood he gets arrested and our house is raided by soldiers or this settler who has turned our lives into a living hell.”

As for Ali, he is waiting for his court session, which is scheduled for the beginning of 2023. He will be at the mercy and whim of the court that day, which will rule in favor of his release, renewal of his house arrest or actual prison time. Ali says that if he is sentenced again, he would rather be given a specific amount of jail time than open-ended house arrest.

Facts and figures

The Committee for Prisoners’ Families in Jerusalem note that Israeli occupation authorities issued approximately 2,200 house arrest orders from January 2018 to March 2022, 114 of them for children under 12.

The number of house arrests dropped during 2021 and 2022 after a new wave of unjust Israeli laws, which allow the detention of minors under 14 and to impose harsher punishments on children charged with throwing stones. This gave Israeli police and courts broader powers to continue detaining children and to hold them for longer periods in prison.

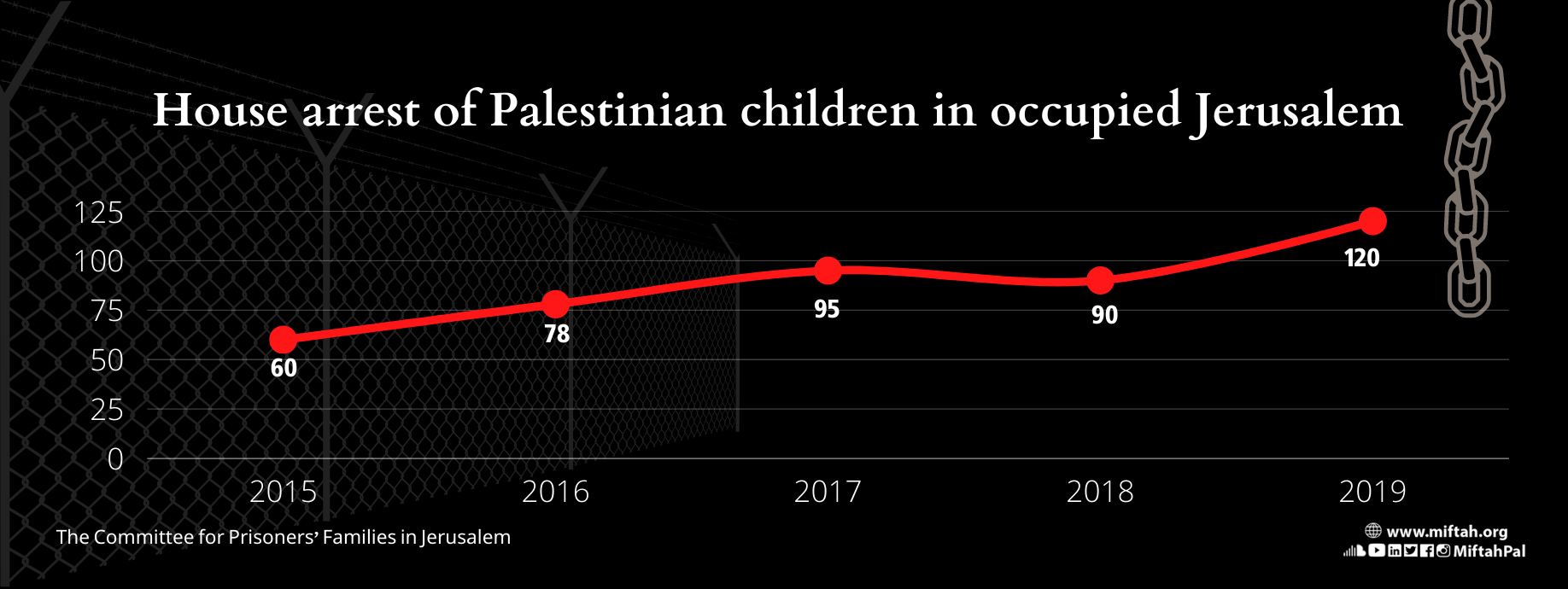

Below is the distribution of cases of children under house arrest according to the Committee for Prisoners’ Families in Jerusalem:

House arrest and international law

Attorney Medhat Deeba says international human rights law and international humanitarian law provide ample space for guaranteeing children’s freedom, safety, protection and dignity. Article 37a of the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child stipulates that, “No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”. Meanwhile, 37b stipulates that, “No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily.”. The same article confirms that “the arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time”, in addition to the right to challenge the legality of the deprivation of his or her liberty before a court or other competent, independent and impartial authority.”

The Fourth Geneva Convention calls for children to be removed from targeted areas in the case of armed conflict and for protecting them from the impact of war. However, in the case of house arrest, he says, the exact opposite is true. Israel takes arrest as its first option with children and treats them as adults. “They are beaten and humiliated from the moment of their arrest and they are then questioned and interrogated without the presence of a lawyer or their parents, in clear violation of international law.”

Once the child’s interrogation is over, court proceedings begin. The child is detained at home as a first option, for a lengthy period of time that could exceed a year, during which drawn-out court measures are conducted. Then, the moment the child is sentenced to jail time (if he is indicted) the period of his house arrest is not deducted from his sentence, which could range anywhere from three to six months.